The post-war years of the 20th century were a real heyday for the printing industry. Offset printing began to develop very quickly. But offset printing is not just about the machine. It is also labour-intensive plate processes, during which it is necessary to take into account a million different nuances, so that the printer did his part of the work without errors.

One of the inventions, without which offset printing would never have become what we know it to be, was the phototypesetter.

What’s the point of developing high-speed offset printing machines if the plate processes can’t keep up with the speed of printing?

As we have gone into the post-war history of offset printing, it is necessary to mention a now largely forgotten but extremely important device, without which the revolution in printing would not have been possible.

What is it and why is it needed?

The first phototypesetter, also known as the photocomposer, was a revolutionary step in printing that replaced the traditional method of typesetting based on the use of metal lettering.

The first phototypesetter, also known as the photocomposer, was a revolutionary step in printing that replaced the traditional method of typesetting based on the use of metal lettering.

The appearance of this device on the market can only be compared to the appearance of a font from the time of Johannes Gutenberg. Letters and their lettering were known to everyone, but how to make them so that they would be many, they would be the same shape, and they would be in the right order?

At the time of the invention of phototypesetting, there was only manual typesetting and line-casting linotype. There were no printers, no computers, not even files! It was all analogue. And at each of the steps it was possible to make a mistake, which would then affect the final result. The Computer-to-film or Computer-to-plate devices we know today were still a long way off.

What the ‘classic’ form preparation process looked like

The process of making text plates for offset printing in a ‘classic’ way looked pretty fancy. Assembled by hand typing, or cast on Linotype, the lines were used to form a page. The operator would then mount the resulting pages on the thaler of a flatbed proofing machine for letterpress printing, and make several impressions. It was important to get a quality print with all the indents needed for the stitching process. The machine’s paper deckle had to be glued with pieces of seasoning sheets to compensate for the different heights of the line elements. And finally, the black ink had to be rolled and the impression made on paper as white as possible.

Do you think that’s all? Not so: then the sheets had to be photographed in a projection camera (like on this picture) onto photographic film and developed. Then the resulting film served as a basis for exposing the plate itself for the offset printing. It was also developed, and only after that it was given to the printer of the offset machine. How the copying layer of the plate was made in the printing house is a separate story…

Do you think that’s all? Not so: then the sheets had to be photographed in a projection camera (like on this picture) onto photographic film and developed. Then the resulting film served as a basis for exposing the plate itself for the offset printing. It was also developed, and only after that it was given to the printer of the offset machine. How the copying layer of the plate was made in the printing house is a separate story…

The new device allowed to put letters directly on the photographic film, bypassing the long process of casting. Not only forms for offset printing were made on the basis of photographic film. They were also suitable for production of stereotypes for high-speed newspaper machines for letterpress printing. That is why even in the mid-90s this technology was not an anachronism in large printing houses.

However, the new device coped with texts, which is not the case with four-colour images. A full-colour sample (a painted poster, a colour photograph on a paper medium) had to be photographed on a projection machine behind four different filters until the appearance in the 80s of the Desktop Publishing System based on high-speed computers with high-quality scanners.

History and development of the first phototypesetter

The problem of multiple storage media until the image hits the paper bothered our distant ancestors as well. The priority in the invention and practical implementation of the phototypesetting machine belongs to the Russian inventor V.A. Gassiev. In 1894 he designed the world’s first model of a phototypesetting machine. In 1900 the Committee for Technical Affairs granted the inventor an official privilege, thus confirming the originality of his invention.

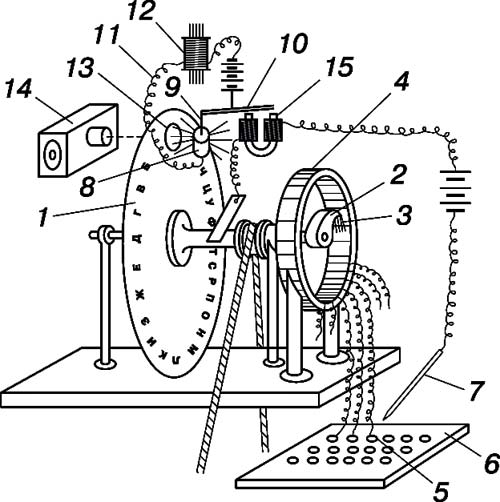

The commutator strips are connected by a conductor with metal keys 5 of the keyboard board 6. At the moment of dialling, the rod 7 comes into contact with the corresponding key of the board. In a glass beaker 8 with mercury is immersed platinum rod 9, fixed on the armature of the electromagnet 10. The mercury and the rod are included in a circuit 11 consisting of a battery and a self-induction coil 12. When pulling the rod out of the mercury, a spark occurs, illuminating through the condenser 13 letter on the disc, caught at this moment in the lens of the camera 14.

The commutator strips are connected by a conductor with metal keys 5 of the keyboard board 6. At the moment of dialling, the rod 7 comes into contact with the corresponding key of the board. In a glass beaker 8 with mercury is immersed platinum rod 9, fixed on the armature of the electromagnet 10. The mercury and the rod are included in a circuit 11 consisting of a battery and a self-induction coil 12. When pulling the rod out of the mercury, a spark occurs, illuminating through the condenser 13 letter on the disc, caught at this moment in the lens of the camera 14.

Figure 1. The first model of a phototypesetting machine built by V.A. Gassiev

The coincidence of the letter with the optical axis of the lens is determined by the position of the brush touching the die at that moment. This die is connected to a key on the keyboard board and closes the current of the electromagnet 15. At this moment, a spark is produced. The duration of the discharge, which causes the spark, determines the exposure time for photographing each individual character. In the process of dialing the disc is rotated by the angle corresponding to the position of the next sign. This sign is triggered by a contact rod brought into contact with a key on the keyboard board.

This was the first, but not the only model – later V.A. Gassiev built more than five more models. The last of them was the most perfect. On this machine V.A. Gassiev received a sample of text on photographic material.

Early developments (1940s – 1950s):

Gassiev’s device was as far removed from the needs of production as the first pinhole camera was from modern cameras. The beginning of the 20th century was associated with the active development of letterpress printing. It was not until the 1940s that inventors in pursuit of a faster and cheaper printing process again recalled the pressing problem.

One of the first industrial photocomposers was the Photosetter, developed in 1946 by Intertype Corporation. However, these early devices were bulky and difficult to operate, which limited their distribution.

The first workable phototypesetting machines were based on Linotype typesetting machines principle. They provided mechanical phototypesetting of separate lines and facets of text. All main technological operations were performed by mechanical systems. Representation of font characters was carried out in analogue form on real font carriers, which were photomatrixes. Each photomatrix contained a negative image of one character and was similar in shape and size to a matrix of a linotype or monotype. The output of the sign on the optical axis was carried out mechanically, and the scaling of the sign during its photographing – by changing the magnification factor of the optical system. In optical-mechanical typesetting machines the creation of the hidden photographic image of text lines was made by means of letter-by-letter photographing of the image of signs of photomatrixes, which were stationary at the moment of photographing.

The output of font signs on the optical axis, i.e. setting the signs in the photographic position, was controlled by the operator who directly entered text information from the keyboard. Line formation was semi-automatic: at the end of typing a line of text the operator decided to end it and gave a corresponding command, and the mechanical system performed the calculation of switching off (bringing the line to the specified format) according to this command.

The output of font signs on the optical axis, i.e. setting the signs in the photographic position, was controlled by the operator who directly entered text information from the keyboard. Line formation was semi-automatic: at the end of typing a line of text the operator decided to end it and gave a corresponding command, and the mechanical system performed the calculation of switching off (bringing the line to the specified format) according to this command.

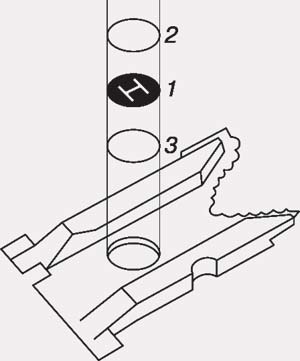

Figure 2. Photomatrix of the ‘Photosetter’ machine: 1 – negative image; 2 and 3 – transparent films

The photo matrices used in the ‘Photosetter’ were similar in shape and size to the linotype matrices. On the wide side faces of the photo matrixes the film with the negative image of the sign is fixed, and on the narrow faces there is a control point and a slot for adjustment during photography.

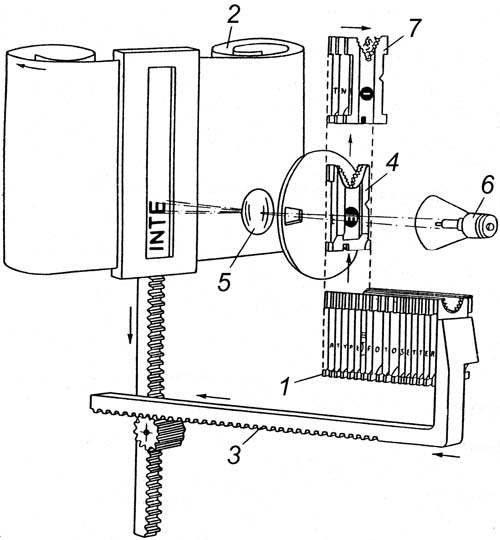

The camera of the phototypesetting machine (Fig. 3), constructed on the basis of the linotype, consisted of a vertically moving removable cassette, a turret with eight lenses, and a mechanism that set the photomatrices (one at a time) in front of the lens, where they were held for projection and then transferred to the distributor.

Figure 3. Schematic diagram of the process of photographing a line in an optical-mechanical phototypesetting machine ‘Photosetter’

Figure 3. Schematic diagram of the process of photographing a line in an optical-mechanical phototypesetting machine ‘Photosetter’

In this case the photomatrices were similar to linotype ones, except that instead of a recessed image of the sign on their wide side edges there was a small window with a fixed film with a negative image of the font sign.

After lifting the workbench, the line from the photomatrixes 1 entered the intermediate channel, where the switching device fixed the size of the unfilled part of the format. At the same time the film cassette 2 was setin the upper position and the gear drive was coupled with the transport slides 3. As the photographic matrices were fed upwards one by one, the cassette was lowered each time by the thickness of the given photographic matrix.

At lifting the next photomatrix 4 stopped in front of the lens 5, centred and illuminated by a beam of light from the lamp 6, which transmitted the image of the font character to the photosensitive film with the required magnification depending on the typing style and characters on the photomatrix. After projection, the photomatrices were assembled into a line 7 and transferred to distribution through the magazine channels in the same manner as in a line-drawing typesetting machine.

Photon and Lumitype (1950s to 1960s):

In the 1950s, a more advanced model called the Photon entered the market. The developer of this machine was Swedish engineer Helge Johansson. The Photon was the first commercially successful phototypesetting device. Its main advantage was that it used a special rotating disc of type that projected an image of characters onto photographic film using a light source.

In parallel, the Lumitype project (sometimes also called Lumitype-Photon), developed by René Igolin and Louis Moiron in the late 1940s and early 1950s, was developing in France. This system also used light to create images of characters on photosensitive material. The Lumitype was the first machine that was able to achieve high speed operation that far exceeded the speed of traditional typesetting methods.

In parallel, the Lumitype project (sometimes also called Lumitype-Photon), developed by René Igolin and Louis Moiron in the late 1940s and early 1950s, was developing in France. This system also used light to create images of characters on photosensitive material. The Lumitype was the first machine that was able to achieve high speed operation that far exceeded the speed of traditional typesetting methods.

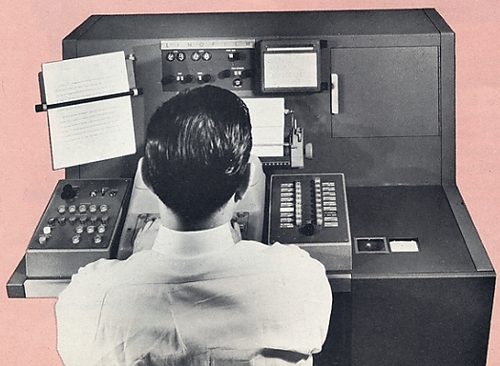

The Lumitype-Photon phototypesetting machine shown on picture is located in the Musée de l’imprimerie et de la communication graphique, 13 rue de la Poulaillerie, 69002 Lyon, France. This system was invented in Lyon by René Higonnet and Louis Moyroud.

Linofilm and further development (1960s to 1970s):

In the 1960s, Linotype developed the Linofilm phototypesetting machine, which became one of the most popular in its class. It offered high quality typesetting and flexibility, which enabled it to gain a significant market share.

The Linofilm used the principle of a rotating drum with a set of typefaces that were illuminated and projected onto photographic film.

The Linofilm used the principle of a rotating drum with a set of typefaces that were illuminated and projected onto photographic film.

The phototypesetting machines worked as follows: text was entered manually or with punch cards, after which the system projected light through optical patterns (fonts) onto photographic film. The resulting images of letters formed text lines, which were then processed in photo and chemical processes to produce printing plates. These plates were used in printing machines to mass produce print runs.

Impact on printing industry

The use of electronic and microprocessor technology in the 80s of the last century made it possible to automate a number of technological operations performed by the phototypesetting machine: changing the typing style according to the code of the corresponding command, entering and storing information about the widths of font characters for different basic typing styles and typefaces, typographic selections in the text according to the code of the corresponding command before its cancellation, calculation of line offsets, formation of paragraph and end lines, formation of lines of a given format taking into account the rules of word division and hyphenation during the processing of the text.

Phototypesetting has had a significant impact on the printing industry, replacing the labour-intensive processes of hot typesetting (when text was formed from metal letters heated and pressed to create an impression). It greatly sped up the typesetting process, improved print quality and allowed the use of more complex fonts and layouts. As a result, phototypesetting was a key step in the development of prepress, and its techniques continued to be refined until the advent of computer systems in the 1980s. But that’s a whole other story.

And to conclude, here is a look at the work of a very rare Photosetter.

Materials used:

Юрий Самарин. История фотонабора: от рассвета до заката. Компьюарт, 4/2012

Dave Hughes. The Linofilm System

History of Information

Available also: